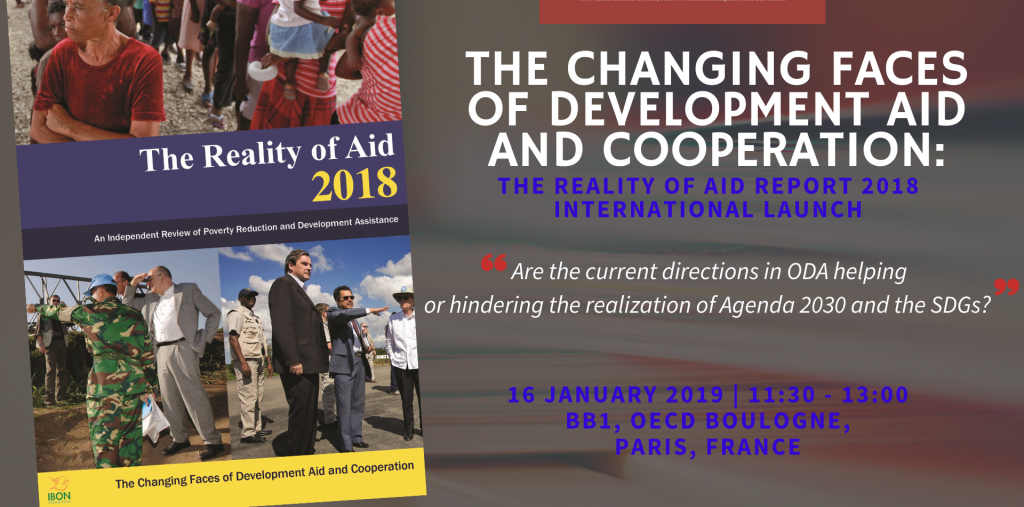

Recent changes in the direction and prospect for international aid in the context of Agenda 2030 lead us to raise questions on the role of Official Development Assistance (ODA) in meeting the financing needs of Agenda 2030. Is ODA fit for this purpose? Are the current directions in ODA helping or hindering the realization of Agenda 2030 and the SDGs?

Many challenges for development in the 21st Century require both a human rights -based and feminist approach to development cooperation. Such an approach is one in which the priorities and practices in providing aid and other forms of development finance are thoroughly informed by human rights standards and inclusive policy dialogue that takes into account the interests of the impoverished and marginalized, and that puts in place comprehensive measures to ensure gender equality and women’s empowerment.

The current uses of aid, however, undermine its very essence as a concessional resource dedicated to human rights and the eradication of poverty.

ODA and private sector resources to achieve the SDGs

There is a general recognition that considerable financial resources are required to meet the financial requirements of the SDGs – although the best way to source these resources is highly contested. Many powerful actors have argued this objective is best accomplished by instrumentalising ODA as a resource to mobilize private sector finance for development through various Private Sector Instruments (PSIs), including those used by specialized Development Finance Institutions (DFIs).

But what do we know about the country level outcomes and impact of private sector finance through PSIs? The short answer is “not enough”. The OECD itself recognises that the evidence base on the impact of blended finance is not yet persuasive: “Little reliable evidence has been produced linking initial blending efforts with proven development results.

The 2018 Reality of Aid Report highlights several case studies that point to some clear directions. The Dibamba Thermal Power Project in Cameroon for example, was partly financed through ODA/blended finance mechanisms. In contravention of requirements under Cameroon law, the project implementers largely ignored the need to address local community services. At the broader economic level, the project has heavily relied on foreign technicians, technology and spare parts, making it difficult for Cameroon to “own” and sustain the project. It collaborates concerns raised elsewhere by civil society, that private sector instruments and blended finance will be associated with an increase in informally tied aid.

With the further investment of ODA to mobilize private finance for development, ODA will only drift away from its core goal of reducing poverty and inequalities.

ODA, security, migration and options for development

Current trends in the allocation of ODA deepen the “militarization of aid” and its diversion to countries and purposes linked to the strategic security interests of major provider countries. For example, since 2002, a movement towards security priorities has been apparent in bilateral aid allocations to Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq, countries of major geo-strategic interest to northern providers.

Despite long-standing DAC principles that ODA should not support financing of military equipment or services, diversion of aid to military and security spending persists. In fact, Korea uses ODA to support police training by the Korean National Police Agency in several Asian countries. Training police forces with ODA resources has been a growing area of provider activities in implementing international security policies. Korean critics suggest that in South Korea, protest-management skills training and Korean-made equipment quash dissent and quell democratization rallies such as in The Philippines and in South Korea itself. Training police forces with ODA resources has been a growing area of provider activities in implementing international security policies.

ODA and responding to the acute challenges of climate change

Climate change can hamper development results and development choices can also change the Earth’s climate by controlling or releasing the carbon emissions in the atmosphere. The international community has been facing many issues in managing climate change, while also pushing to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. The fragmented nature of the global climate finance landscape increases the challenges associated with accessing finance and reduces overall efficiencies (Sachs & Schmidt-Traub, 2013).

With the imperative to scale up climate finance after 2020, all countries and stakeholders must make new and concerted efforts to agree on new targets beyond the $100 billion and to consider new and innovative sources for climate finance. Examples of the latter include carbon pricing for aviation, a financial transaction tax or an equitable fossil fuel extraction levy. Developed countries must honour their previous commitments to new and additional public resources for international climate finance, while also increasing their ODA for other purposes.

South-South Development Cooperation in development finance

For over four decades emerging developing countries have been engaging in SSDC, primarily through technical exchanges and the sharing of knowledge, among many other forms, in addressing development challenges. However, to fulfill its promise, CSO activists in the South emphasize that SSDC must be held to standards that are embedded in SSDC principles. It is essential to strengthen capacities to support inclusive partnerships, greater transparency, and people’s rights. While recognizing SSDC as an invaluable resource, it must also be emphasized that it is not an alternative to fully transformed and substantially increased North-South development cooperation.

China’s SSDC in Kenya and Angola for example, which responds to African countries’ need for infrastructure, is largely driven by China’s economic interests, companies and technologies.

Issues relating to human rights [such as labour rights] or people’s empowerment remain aspirations that are alluded to, but are not tackled directly by either side of the cooperation.

Safeguarding the integrity of ODA and Transforming Development Cooperation: A Reality of Aid Action Agenda:

In the context of Agenda 2030, aid providers must live up to their promise that aid is a resource devoted to reducing poverty and inequalities. They must transform their allocations and aid practices in ways that support collaborative initiatives as well as equal and inclusive partnerships for these purposes. They must work within the framework of development effectiveness principles, human rights and feminist approaches. National democratic ownership of development strategies, plans and action in developing countries should be confirmed in practice as the foundation for effective development cooperation.

The Reality of Aid Network is putting forward a Ten-Point Action Agenda for retooling ODA for the transformation of development cooperation:

- Achieving the 0.7% Target – DAC providers that have not achieved the 0.7% of GNI UN target for ODA must set out a plan to do so without further delay.

- Addressing the needs of the least developed, low income, fragile and conflict-affected countries – As DAC donors move towards the 0.7% target, they must also meet the long-standing commitment to allocate up to 0.2% of their GNI to Least Developed Countries (LDCs).

- Establishing a rights -based framework – The allocation of all forms of development finance, but particularly ODA and other concessional sources, must be designed and measured against four development effectiveness principles, human rights standards.

- Mainstreaming gender equality and women’s empowerment – Providers of ODA and other forms of concessional development finance (e.g. SSDC) must demonstrably mainstream gender equality and women’s empowerment in all dimensions of development cooperation projects, programs and policies.

- Addressing other identity-based inequalities – Providers of ODA must develop strategies to guide increased efforts to tackle all forms of inequalities, such as those based on economic marginalization, disabilities, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity or age.

- Reversing the shrinking and closing space for CSOs as development actors – All actors for development – governments, provider agencies, parliamentarians, INGOs – must proactively challenge the increasing regulatory, policy and physical attacks on civil society organizations, human rights defenders, indigenous groups and environmental activists.

- Implementing clear policies for ODA to improve its quality as a development resource – Development and aid effectiveness principles require practical reforms to strengthen partner ownership to achieve the priorities of ODA.

- Deploying ODA to support private sector initiatives and catalyze private sector funding –ODA should only be deployed for provider Private Sector Instruments (PSIs) in projects/activities that can be directly related to building capacities of developing country private sector actors to demonstrably improve the situations of people living in poverty.

- Rejecting the militarization and securitization of aid – In responding to humanitarian situations and the development needs of countries with high levels of poverty, conflict and fragility, providers should avoid shaping their strategies and aid initiatives according to their own foreign policy, geo-political and security (migration and counter-terrorism) interests.

- Responding to the acute and growing challenges from climate change – All Parties should reach agreement on a post-2020 climate-financing framework for developing countries that meets the growing challenges they face in adaptation, mitigation as well as Loss and Damage. While concessional climate finance meets the criteria for ODA, the DAC should account for principal purpose climate finance separate from its reporting of ODA, acknowledging the UNFCCC principle of “new and additional.” The UNFCCC should develop clear guidance for all Parties on defining finance for adaptation, mitigation and Loss and Damage.

DOWNLOAD 2018 RoA Global Annual Report