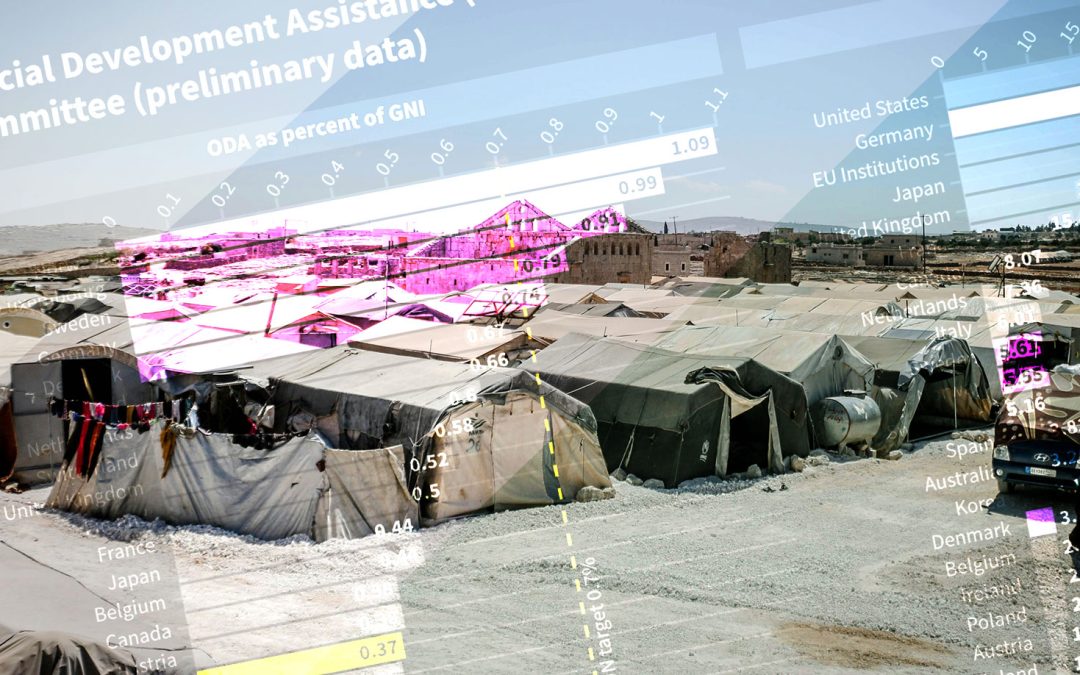

The 2023 Official Development Assistance (ODA) preliminary data reveal that numbers were majorly influenced by humanitarian aid, particularly aid to Ukraine. Civil society highlights how members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development – Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) prioritized domestic interests over international needs when allocating their foreign aid funding in 2023. The continuous geopoliticization of aid, as seen where USD 223.7 billion in ODA was spent primarily on aiding Ukraine and refugees living within major donor countries – such as Germany, the United States, United Kingdom, etc. – undermines efforts to tackle other severe global challenges as this diverts resources from marginalized regions. The DAC plays a crucial role in assisting developing countries in providing economic resources to manage crises, such as war and conflicts and natural disasters. However, their strategies in distributing aid often results in an unequal donor-recipient dynamic, impacting the most vulnerable of the Global South.

The 0.7% threshold: focus on Asia Pacific

In 2023, five donor countries, including Denmark, Germany, Luxembourg, Norway, and Sweden, have allocated more than 0.7% of their GNI to ODA in support of international development initiatives – that is an additional one donor country compared to 2022, after Denmark increased its aid by USD 1 billion last year. Civil society reports that two out of five of the donor countries who meet the 0.7% threshold only did so after counting in-donor refugee costs (IDRC) as part of ODA, which has always been controversial. On the other hand, recent global issues seem to not influence Australia’s aid in 2023 which remains the same as 2022 at 0.19%. Australia is 0.51% away from meeting the 0.7% target; New Zealand fell short by 0.4% and Japan by 0.26%. South Korea needs to up its aid by 0.52% more to achieve the minimum ODA commitment. Asia Pacific donors provided an overall low percentage of ODA to their neighboring countries.

The ODA provided by Australia reached USD 3.25 billion in total. On a net disbursement basis, Australia spent USD 2.7 billion on bilateral development and USD 0.5 billion on multilateral ODA. Meanwhile, South Korea provided a total of USD 3.1 billion in ODA, where USD 1 million was directed to in-donor refugee costs. South Korea’s ODA increased in 2023 due to the rise in its multilateral contributions with a total amount of USD 2.41 billion on a net disbursement basis, but is still not enough to meet the threshold.

In terms of ODA as a percent of GNI, Australia (0.19%) and South Korea (0.18%) find themselves positioned at the bottom yet again, ranking 26 and 28 on the list of DAC members, respectively. On the other hand, with regards to GNI, New Zealand rose from 0.22% in 2022 to 0.3% in 2023, with an additional USD 0.25 billion ODA. Even so, it must not be disregarded that a significant portion of New Zealand’s ODA is channeled to refugee costs spent within the country; that being USD 13 million in 2023.

While Japan surpasses other Asia Pacific donors on the upper end of the list, its performance remains unsatisfactory. A trend on Japan’s ODA, according to Development Initiatives, is that it grew 15% but is said to be an initiative to counteract the influence of China in the region. Japan does, however, provide a disproportionately small amount of aid to least developed countries (LDCs) in contrast to main donors, with a significant portion of this aid provided in the form of concessional loans. Hence, despite an overall increase in Japan’s ODA, this distribution reveals inequalities in aid allocation. The impact on least developed countries, particularly those in the region, remains limited, as they continue to receive only a fraction of the total ODA, falling short on targets. ODA amounting to USD 37 billion, which is only 14.8% of total ODA, was allotted to 46 LDCs; 23 of which are in Asia Pacific. And yet, despite a slight increase in bilateral aid, assistance to these LDCs has not entirely recovered from previous cuts.

Humanitarian aid to Ukraine dominates ODA

Humanitarian aid having increased by 4.8%, makes up a significant portion of the total ODA allocation in 2023. With the amount of USD 20 billion (9% of total ODA), DAC member countries allocated 84% of ODA to Ukraine for developmental purposes and 16% for humanitarian purposes, resulting in a 9% increase in real terms from 2022. Year 2023 recorded bilateral ODA for Ukraine as the largest amount of aid given to a single country in a single year in history.

European Union institutions also contributed significant help to Ukraine in addition to aid from DAC members, investing an additional USD 20.5 billion on concessional loans to sustain macroeconomic stability. While this shows donors’ commitment to Ukraine’s development and humanitarian concerns, other regions in severe conflicts face lack of support as their aid generally decreases. It is therefore crucial for the OECD-DAC to reassess aid distribution and to live up to their main purpose of delivering equitable access to aid and fostering stability in the global South.

In-donor refugee costs raise debate

There was a minor decline in in-donor refugee costs which was compensated by increases in humanitarian aid to Ukraine, so otherwise, ODA remains stable in 2023. The year 2023 marks the fifth consecutive year ODA has had an increase since 2019, consistently breaking its own records for half a decade. This steady rise in ODA, most especially the surge in Ukraine assistance, illustrates some commitment from donor countries in supporting (developing) nations despite the presence of global economic challenges. However, this is not outstanding viz the promises. As previously reported, despite the need for more enhanced action, ODA figures for 2022 and 2023 are comparatively similar to those of previous years. Despite an increase in total ODA, the in-donor refugee costs remain questioned, with one of its shortcomings being falling short on spendings in 2023 compared to previous years.

As permissible by the DAC guidelines, some donor countries count the costs of temporary sustenance to refugees in developing countries as ODA. CSOs have raised objections to this inclusion as in-donor refugee costs should not qualify as aid. Even though IDRC still constitutes 13.8% of DAC member countries’ total ODA after accounting the slight decrease from USD 31 billion in 2022 to USD 30.967 billion in 2023, concerns regarding domestic aid allocation resurface.

Civil society asserts that the inclusion of IDRC distorts ODA figures as these create a misleading impression of aid reaching or trickling down to low and middle-income countries when in fact, said aid never crossed borders. Regulating these costs could potentially channel more funds toward core development projects, which are crucial for tackling poverty and forced displacement. However, if aid to in-donor costs remains high, a larger portion of the funds are instead utilized to further the interests of donor countries, undermining the original purpose of ODA. Moreover, because in-donor costs are included in estimates of foreign aid, some critics question the reliability of published aid figures.

Upholding ODA Integrity in Asia Pacific

Once more, CSOs pressure donors to honor and exceed the 0.7% GNI to ODA target commitment to the Global South. Over again, CSOs stress that humanitarian efforts in least developed countries are continuously undermined as long as aid distribution remains inequitable. For consecutive years, the unfair aid distribution pertains to both diverting funds to humanitarian aid, often at the expense of aid directed to the most vulnerable and marginalized in the Global South who need ODA the most, and incorporating in-donor refugee costs as part of their contributions.

Can the region expect advancement in its development initiatives when ODA numbers reflect the limited efforts and aid contribution of Asia Pacific donors themselves? The gap in aid indicates deeper systemic concerns in allocation of funds and even the prioritization of which sectors and countries to fund, referring to the very few Asia Pacific donors having little influence in the global aid system and the overall inadequate participation from Global South recipients in decision-making processes.

CSOs, therefore, call on Asia Pacific donors to elevate their ODA endeavors. Not only do CSOs persist in urging DAC members among the region to fulfill and surpass their ODA commitments, but also urge them to steadfastly safeguard ODA. One way to do this is to reject the inclusion of in-donor refugee costs as ODA. While accountability does not only rest among Asia Pacific donors, their presence at the decision-making forum serves to amplify the demands of the region. Asia Pacific donors must use their platform to ensure that development cooperation genuinely corresponds to regional and global needs. By upholding the integrity of ODA, they can fulfill their commitments to their neighbors which is for the benefit of the overall advancement and sustainability of Asia Pacific.