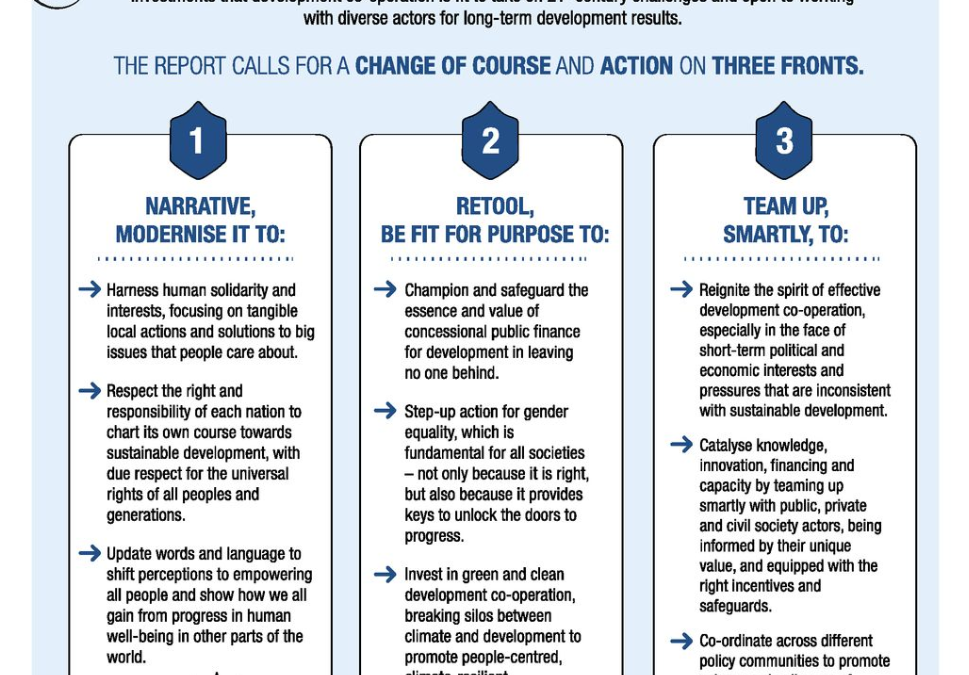

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), through its 2019 Development Cooperation Report, urges donor governments and their relevant agencies to change the course and action in development cooperation on three fronts: 1) modernise the narrative, 2) re-tool to be fit for purpose, and 3) team up with diverse actors to promote coherence.

In the same report, the OECD laid out recommendations on how donor governments can “re-shape” their strategies in advancing development cooperation. However, these set of recommendations have long been asserted by civil society organisations (CSOs) to governments, multilateral institutions, and other development networks and platforms. In other words, these are not new.

For instance, the first front on modernising the narrative, the OECD calls donor governments and agencies to “respect the right and responsibility of each nation to chart its own course towards sustainable development”. However, this narrative is already part of the established development effectiveness principles which all development actors are expected to heed.

The second front, re-tool to make sure that development cooperation is fit for purpose, includes the recommendation to “champion and safeguard the essence and value of concessional public finance”. This is actually a long-standing call of The Reality of Aid Network (RoA) and many other CSOs in order to fund sustainable development. However, donor governments continue to utilise public finance to leverage private sector investments and RoA has produced several evidence-based research on the negative impacts of various private sector interventions.

Lastly, the third front calls for coherence among diverse actors, primarily the public sector, private sector, and civil society, to work together for development cooperation. Despite several narratives on the negative impacts of private sector interventions in the Global South, the OECD continues to encourage partnerships with the private sector that lack monitoring, analysis, and transparent and accountable mechanisms.

Despite the long-standing call of CSOs to foster and implement development cooperation on a human rights-based, people-powered approach, governments (both donor and recipient) seem to take another direction where outcomes are nowhere near the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the negative impacts to communities are only exacerbated.

For example, members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), the group of the world’s leading development cooperation providers, acknowledged the increasing crises in fragile states and the need to level up their efforts in solving conflict, thus providing USD 74.3 billion Official Development Assistance (ODA) in 2017. According to the OECD 2019 Report, “fragile contexts received 68% of earmarked ODA – the highest in six years”, but of this, only 2% or USD 1.8 billion is allotted for conflict prevention.

In 2016, the cost for containing violence was already at USD 13.6 trillion, according to the Institute for Economics and Peace, but then until now, humanitarian assistance remains the priority even if development actors have long recognised that spending on conflict prevention will save the world of around USD 70 billion per year, at least in the most optimistic scenario (Pathways for Peace 2018).

The Asia-Pacific region, in particular, is mired with ever increasing conflict and fragility, which are seen as consequences of civil wars supported by some donor countries themselves, authoritarian governments, and the corporate capture of development. The US, in particular, “tends to prioritize countries where it has a strategic interest”, making Israel its largest beneficiary of foreign assistance (Reality of Aid Report 2018). Additionally, American troops have been deployed to “curb” social unrest in Palestine.

Another expression of donor governments’ indirect support for civil wars is that of United Kingdom’s arms deal with Saudi Arabia, which houses Yemen President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi as he is in exile. Dubbed as the Saudi-led coalition, the Saudi Arabian government and Hadi have been leading military intervention against the Houthis, an Islamic political and armed movement supposedly fighting for the liberation of Yemen.

UK has a reportedly £4.7 billion (roughly USD 6 billion) worth of arms deal with Saudi Arabia and has also supplied military training to the aggressor. Such weapons and trainings have been used to amplify direct attacks on the Yemen population. In 2017, about 7 million civilians were in the brink of famine while 683 children became casualties of airstrikes, making Yemen on top of the world’s worst humanitarian crisis (The Guardian 2017).

Indeed, vulnerable groups are the most affected of all. Women and children, especially young girls, are highly susceptible to fragility. The OECD cites, “In conflict situations, for instance, young girls are 2.5 times more at risk of not attending school than boys; nine out of the ten countries with the highest child marriage rates are considered fragile or extremely fragile.”

Aid allocated for gender and women’s empowerment, however, is not enough to address structural inequalities that deepen conflict and fragility. In 2017, the DAC disbursed USD 46.4 billion, equivalent to 39% of their combined bilateral ODA, for gender equality. Although this has been the highest allocation in decades, it remains inadequate to mainstream gender and women issues (OECD 2019).

In effect, fragile countries in the region continue to be impoverished, ill prepared for disasters, prone to terrorism and militarisation, and vulnerable to forced displacement.

Conflict and fragility must be confronted with utmost urgency. As reported in the States of Fragility 2018, the OECD recognizes that “without significant action 34% of the global population, or 3.3 billion people, will be living in fragile contexts by 2050”. We do not want to live to see the next generation suffer from the problems we could have dealt with today.

To encourage donor governments to support programs addressing conflict and fragility, the DAC approved in February 2019 the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus Recommendation, a non-binding legal document that aims to promote coherent solutions among various actors, including International Finance Institutions (IFIs) and the private sector. According to the OECD, “This recommendation requires a shared approach that prioritises prevention always, development wherever possible and humanitarian action when necessary.”

The Nexus Recommendation, however, forwards mechanisms to incentivise IFIs and the private sector with the belief that governments and multilateral institutions cannot successfully achieve the goals of the triple nexus without the right kind or mix of development financing. As of writing, the OECD, through its subsidiary body, the International Network on Conflict and Fragility (INCAF), is yet to design a roadmap for the Nexus Recommendation implementation.

The challenge with incentivising IFIs and the private sector is that governments lose focus on their commitment to provide 0.7% of Gross National Income (GNI) as ODA for sustainable, long-term development cooperation. The Reality of Aid Report 2018 provides several narratives on how donor governments use ODA resources to mobilise private finance. Netherlands, for instance, allocated “more than 10% Dutch ODA in 2017” for private sector programming, and “half of these funds were made available to Dutch businesses to promote Dutch commercial interests abroad”.

And yet, with “increased quantities and significantly improved effectiveness… ODA can be and must be a leading and essential component of poverty eradication” (Reality of Aid Report 2018). Despite the increasing ODA of donor countries, budget allocation to aid programs for fragile states and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) is decreasing. Leveraging the private sector finance is no help either. CONCORD’s AidWatch 2019 reported that “more than 77% of private finance mobilised by ODA went to middle-income countries”, underscoring the drive for profit of the private sector while sidelining the delivery of sustainable development.

The truth is, peace programs are not palatable to the private sector because these are not profitable. In fact, corporations have been reportedly contributing to widening inequality and worsening conflict in communities. Moreover, according to a GPEDC 2018 paper, “Research on aid effectiveness shows that out of 900 analysed projects involving the private sector, only 4% of them focused on the poorest”.

Development cooperation should not promote the neoliberal model of development, which sees development as a profiteering opportunity more than public service. As such, private sector interventions with high regard for returns and profits only allow conflict, fragility, and inequality to persist. Instead of putting much effort to funding actions that are reactive and unsustainable for the affected communities, development actors should utilize public finance effectively and efficiently to achieve long-term gains.

Narratives from Asia-Pacific CSOs prove how conflict is intensified by militarisation and human rights violations resulting from ODA-supported private sector investments. Women, youth, Indigenous Peoples, and other marginalised sectors in the region are pushed to further oppression and poverty, and this cycle will continue as long as the private sector can get away from accountability for their actions.

This is not to say that donor and partner governments are not culpable. The EU, for example, has specific interest on migration and security issues. As a result, there are “severe risks of diverting financing from priorities vital for reducing poverty, while strengthening EU relations with governments who violate human rights and repress their citizens. Moreover, such interest “brings severe risks of funding being directed to militia or security sector actors involved in border patrol” (AidWatch 2019).

“What must be done, then?” is always the question that CSOs have an answer to offer. To address conflict and fragility, in particular, development cooperation must focus on prevention and governments must scrap policies that would only perpetuate conflict, including those that encourage public-private partnerships that transform social services into profitable business.

Development actors (governments, multilateral institutions, IFIs, private sector, etc.) should honor development effectiveness principles of democratic ownership, focus on results, inclusive partnerships, and mutual transparency and accountability. Moreover, for development programs to be truly sustainable, fair, and democratic, a human rights-based, people-powered approach must be taken in designing, implementing, and evaluating programs.

For the effective and efficient use of ODA as valuable resource for development cooperation, RoA highlights a ten-point action agenda that it puts forward in several policy arenas (Reality of Aid Report 2018):

- Achieve the 0.7% of GNI for ODA

- Address the needs of the least developed, low income, fragile and conflict-affected countries – DAC donors’ 0.2% of GNI must be allocated for LDCs

- Establish a rights-based framework – development programs must be designed and measured against development effectiveness principles and human rights standards

- Mainstream gender equality and women’s empowerment

- Address other identity-based inequalities

- Reverse the shrinking and closing space for CSOs as development actors

- Implement clear policies for ODA to improve its quality as a development resource

- Deploy ODA to support private sector initiatives that can be directly related to building the capacities of development countries’ private sector, whose actions should demonstrably improve the situations of people living in poverty

- Reject militarisation and securitisation of aid

- Respond to the acute growing challenges from climate change